|

|

| 'Like' us on Facebook | Follow us: |

Posted on: Sept 12, 2013

THIS 9/11 AND THE OTHER 9/11s

The Potent Messages from 'HIS'tory

Part-2

The second significant 9/11 (after Vivekananda's 9/11 1893 speech) concerns another champion of India's eternal values. The crusader, who overwhelmed the mighty British empire with the power of his conviction on the principles which stand as the pillars of Indian culture.

A remarkable personality, who revolutionized the minds of the masses and awakened in them the possibility of waging a war without the use of a single weapon, leading them to a glorious triumph. The grateful nation conferred on him the title – Father of the Nation.

The story of Mahatma Gandhi and his weapons of Truth and Non-violence interestingly has its origins too in a 9/11 – September 11, 1906. The venue this time is South Africa.

The Shaping of South Africa's Demographics

In fact Prof. Venkataraman had mentioned about this in a talk on Radio Sai in 2004. Narrating this story in detail he said:

“The story of South Africa until 9/11 1906 is something like this.

|

|

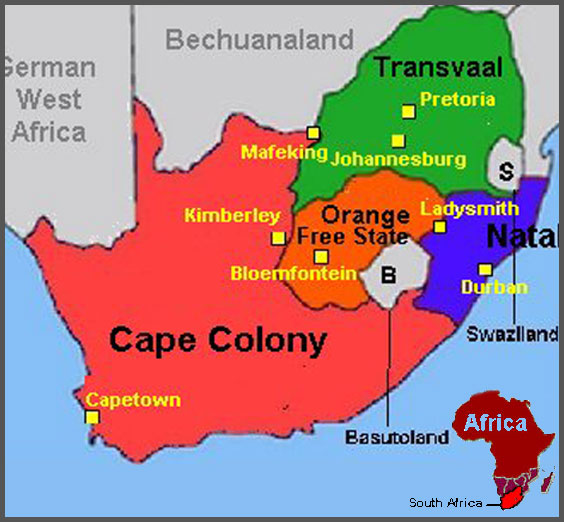

| The political map of South Africa in early twentieth century. |

It all started in the 19th century, with the colonisation of South Africa in particular. And two European powers competed for control of that part of the African continent.

The British defeated the Dutch in the Boer War. South Africa now became a colony under the British Crown, with however, a significant white population of Dutch origin.

Of course, the country was mainly populated by the indigenous Africans. And there were also many Asians mostly from India. The latter belonged to two distinct groups – those employed in menial labour and those in the service sector.

The British took tens of thousands of labourers to South Africa and this was, so to speak, the first wave of Indian immigration. Now, these people needed shops and many support services, including doctors, barbers, etc. This need for the service sector led to the second wave of immigration in South Africa.

In fact, Gandhiji went to South Africa as a young barrister to represent an Indian client there in a court case.

Thus, the Indian community in South Africa was, at that time, made up essentially of these two segments.

And what about the whites and the native Africans?

Well, the British knew how to take care of themselves from travel to health to all other needs and conveniences.

As for the native tribes, they managed the way they had for thousands of years – there was no organised service really!

In short, the demographic situation there in the late 19th century was as follows: the Dutch had been defeated no doubt, but the Dutch settlers were accepted as full-fledged members of the white community.

So, the whites of course enjoyed first-class status. The natives were relegated to the bottom of the totem pole – no problems were foreseen in doing so. The natives were 'subhuman' in their opinion, and they had no place except at the bottom.

Coming now to the Indians, they were seen as troublesome, and the law drafted was highly discriminatory and even insulting. The idea was to harass the Indians to the point of forcing them out of South Africa. This was done by requiring all Indians to carry a permit at all times. The permit rule was designed to be obnoxious from the beginning, and it permitted limitless scope for harassment. For example, new-born Indian babies would be taken into detention because they did not have a permit! That is how pitiable the situation was then.

|

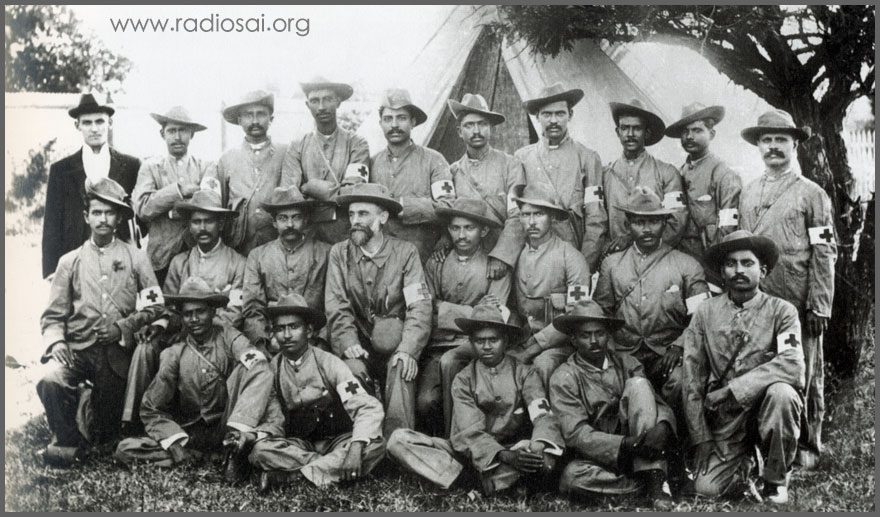

Gandhi (fifth from left in the middle row) with the Indian Ambulance Corps during the Boer War in South Africa, 1899-1900. Once hostilities between Boers and Britons broke out in 1899, Gandhi firmly sided with the Empire and raised an Indian Ambulance Corps comprised of 300 free Indians and 800 indentured labourers. Their work during the conflict won British admiration and as a result Indians believed - mistakenly as it turned out - they would be rewarded with greater political rights once the war ended. Photo Courtesy: 'Gandhi' by Peter Ruhe published by Phaidon |

During this time, to make life even more terrible for Indians, the South African Government proposed a law called the Asiatic Law Amendment Ordinance. This was a draft proposal basically to legalise all the discrimination against the Asians. And it is this that Gandhiji opposed.

However at that time, Gandhiji had not yet taken up cudgels against the British Empire and colonialism – that came later, after his return to India. He was then quite prepared to accept British rule but wanted fairness for all within that system.”

The Birth, Nomenclature and Blossoming of Satyagraha

On August 22, 1906, the Transvaal Government in South Africa under the British Crown gave notice of this new legislation requiring all Indians, Arabs and Turks to register with the government. Fingerprints and identification marks on the person's body were to be recorded in order to obtain a certificate of registration. Those who failed to register could be fined, sent to prison or deported, and this included even little children. At the time, Gandhi worked as a lawyer for a company owned by an Indian Muslim.

Therefore, the way the law was made, it granted divine rights to the whites, condemned the blacks and discriminated against the brown. So how to stop this?

Prof. Venkataraman continues:

“Committed as he was to the due processes of law, Gandhiji attempted legal redress. He wrote to higher authorities in South Africa and to influential Members of the British Parliament. Among those he wrote to was Dadabhai Naoroji, the first Indian to be elected a Member of the British House of Commons. However none of this was effective.

It is at this point that Gandhiji decided to take the next step, which was the beginning of a new chapter in the never-ending fight against human injustice.

So that’s it! The famous Satyagraha movement that was to form the cornerstone of India’s fight for Independence was actually born in South Africa, interestingly enough on 9/11, though of a much earlier era.”

On September 11, 1906, Gandhi called a mass meeting of some 3,000 Transvaal Indians at the Empire Theatre in Johannesburg. The objective was to find ways to resist the Registration Act. He felt the Act was the embodiment of 'hatred for Indians' which if accepted would 'spell absolute ruin for the Indians in South Africa', and therefore resisting it was a 'question of life and death'.

Among the thousands gathered was one Sheth Haji Habib, an old Muslim resident of South Africa. Deeply moved after listening to Gandhiji's speech, Sheth Habib said to the congregation that the Indians had to pass this resolution with God as witness and could never yield a cowardly submission to such a degrading legislation.

In the book 'Satyagraha in South Africa' Gandhiji reminisces that day and writes: “He (Sheth Habib) then went on to solemnly declare in the name of God that he would never submit to that law and advised all present to do likewise.”

|

|

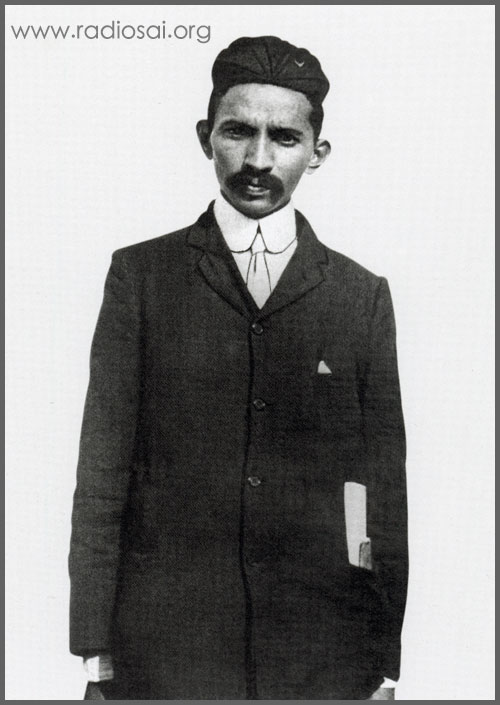

| Gandhiji in Johannesburg, Transvaal, 1900. Indians encountered the most severe discrimination in Transvaal, where they could not trade or reside except in designated locations, described by the London Times as 'ghettos'. Photo Courtesy: 'Gandhi' by Peter Ruhe published by Phaidon |

This was significant because here was a respected member of the Indian community asserting his decision to act in defiance and expressing his willingness to suffer the consequences in a spiritually-endowed fight for justice in the name of God.

In fact Gandhi was quite taken aback by Habib's suggestion. He writes:

“The world imagines an ordinary resolution and an oath in the name of God to be poles asunder.

A man who makes an ordinary resolution is not ashamed of himself when he deviates from it, but a man who violates an oath administered to him is not only ashamed of himself but is also looked upon by society as a sinner.... Although I had no intention of taking an oath or inviting others to do so when I went for the meeting, I warmly approved of the Sheth's suggestion.”

Once the meeting took this turn Gandhiji felt it was his duty to explain to the community what taking an oath really meant practically, and if they were sufficiently prepared to take such a pledge. He told them:

“We all believe in one and the same God, the differences of nomenclature in Hinduism and Islam notwithstanding. To pledge ourselves or to take an oath in the name of that God or with Him as witness is not something to be trifled with. If having taken such an oath we violate our pledge we are guilty before God and man.

Personally I hold that a man, who deliberately and intelligently takes a pledge and then breaks it, forfeits his manhood...

A man who takes a vow every now and then is sure to stumble. But if I can imagine a crisis in the history of the Indian community of South Africa when it would be in the fitness of things to take pledges, that crisis is surely now...

There is wisdom in taking serious steps with great caution and hesitation. But caution and hesitation have their limits, and we have now passed them. The Government has taken leave of all sense of decency. We would only be betraying our unworthiness and cowardice, if we cannot stake our all in the face of the conflagration which envelopes us and sit watching it with folded hands...

There is no doubt, therefore, that the present is a proper occasion for taking pledges. But every one of us must think for himself if he has the will and the ability to pledge himself.... Every one must only search his own heart, and if the inner voice assures him that he has the requisite strength to carry him through, only then should he pledge himself and only then will his pledge bear fruit.

It may be that we may not be called upon to suffer at all. But if, on the one hand a man who takes a pledge must be a robust optimist, on the other hand he must be prepared for the worst. Therefore I want to give you an idea of the worst that might happen to us in the present struggle.

Opulent today we may be reduced to abject poverty tomorrow. We may be deported. We may be subjected to starvation and similar hardships in jail, some of us may fall ill and even die. In short, therefore, it is not at all impossible that we may have to endure every hardship that we can imagine, and wisdom lies in pledging ourselves on the understanding that we shall have to suffer all that and worse.

Although we are going to take the pledge as a body, no one should imagine that default on the part of one or many can absolve the rest from their obligation. Every one should fully realize his responsibility, only then pledge himself independently of others and understand that he himself must be true to his pledge even unto death, no matter what others do."

When Gandhiji finished, the community was more charged and enthusiastic than ever before. And before the session concluded all the 3000 of them stood up and with upraised hands took the oath with God as witness not to submit to the ordinance if it became law.

That is how Satyagraha started.

|

| This image was taken in 1908, two years after the origin of Satyagraha in South Africa. Here 2000 registration certificates go up in flames outside the Hamidia Mosque, Johannesburg, 16 August 1908. The bitter opposition to Gandhiji's compromise with Smuts was justified as the Transvaal Government failed to repeal the Act. Undeterred, Gandhiji led a renewed campaign of resistance, which commenced with the public burning of thousands of registration certificates. He widened the campaign by challenging the ban on Indian immigration into Transvaal from Natal with a march across the frontier. Photo Courtesy: 'Gandhi' by Peter Ruhe published by Phaidon |

In fact at that time Gandhiji did not know what name to give to this new movement. Initially he used the term 'passive resistance'. But this was grossly inadequate and often misleading, as 'passive resistance' was viewed as a weapon of the weak and helpless. Gandhiji now wanted a new nomenclature which would convey the strength and power of this idea. Moreover a foreign phrase could hardly pass as current coin among the Indian community there.

So Gandhiji announced a small prize in Indian Opinion for any reader who invented the best designation for this novel struggle. One of the competitors, Mr. Maganlal Gandhi suggested 'Sadagraha' meaning 'firmness in a good cause'. Gandhiji liked the word but it did not fully represent the idea he wanted it to connote. So he changed it to 'Satyagraha', that is, 'The Force born out of Truth and Love or Non-violence'. To put it simply, the Soul Power.

This is how the eternal principles of Truth, Love, Unity and Tolerance were once again demonstrated to the world during this second significant 9/11, just 13 years after the first 9/11 in 1893 when Vivekananda shook and reminded the West of these timeless values.

|

| A Satyagrahi leader, Thambi Naidoo, addressing a meeting of over 6000 people on the Durban Indian Football Ground during the Satyagraha of 1913. A proposed law that effectively declared all non-Christian marriages illegal sparked Gandhi's last and most extensive resistance campaign in South Africa. Photo Courtesy: 'Gandhi' by Peter Ruhe published by Phaidon |

The Cascading Effect of Satyagraha - From Dalai Lama to Barack Obama

And since then Gandhiji's Satyagraha not only liberated 300 million Indians from the over 200-year English rule, but also has inspired a string of revolutions under legendary leaders, from Vinoba Bhave (Bhoodan Movement) to Sunderlal Bahuguna (Chipko Movement), from Martin Luther King Jr to Nelson Mandela, and from Dalai Lama to Aung Suu Kyi.

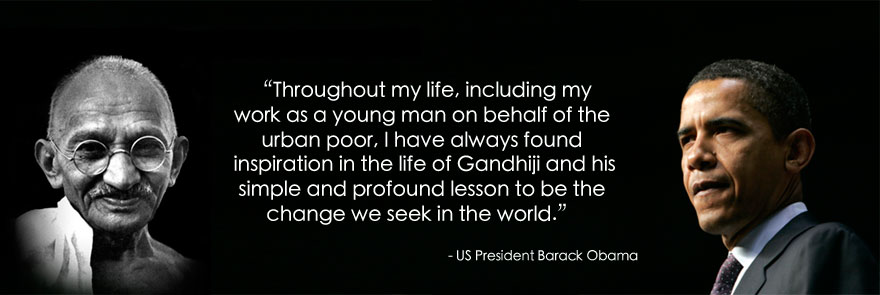

Interestingly, the current US President Barack Obama, during his address at the United Nations General Assembly in September 2012, said:

“It's time to heed the words of Gandhi: 'Intolerance is itself a form of violence and an obstacle to the growth of a true democratic spirit.' Together we must work towards a world where we are strengthened by our differences not defined by them.”

Two years prior to this, when President Obama spoke to the Indian Parliament in New Delhi, he referred to Gandhiji six times and described him as an early, defining influence: “Throughout my life, including my work as a young man on behalf of the urban poor, I have always found inspiration in the life of Gandhiji and his simple and profound lesson to be the change we seek in the world.”

|

Also, in 2009, when a student asked Mr. Obama who he would most like to have dinner with, dead or alive, the President picked the Mahatma:

“He’s somebody who I find a lot of inspiration in. He inspired Dr. King (Martin Luther King), so if it hadn’t been for the non-violent movement in India, you might not have seen the same non-violent movement for civil rights here in the United States.”

In the same year during his Nobel Peace Prize acceptance speech, this first African-American President of the United States once again paid tribute to Gandhiji and his ideals:

“As someone who is a direct consequence of Dr. King's work, I am a living testimony to the moral force of non-violence,” he stated and added, “I know there is nothing weak – nothing passive – nothing naive – in the creed and lives of Gandhi and King.”

It is heartening to know that in the present times one of the most powerful persons on earth has deep reverence for Gandhiji and believes in his Satyagraha. At the same time the reality is that even now large chunks of humanity never seem to be convinced that 9/11s like that of 1893 or 1906 can indeed prevent the 9/11 of 2001.

Somehow, taking the option of peace and reconciliation seems to be a difficult proposition. That is why we see violence being given so many opportunities today but peace gets none. If violence gets 100 chances, peace probably gets only one. Why is it so?

Well, Baba Himself directly has given the answer. And that happened fascinatingly on another 9/11. When was it? What did He say? That story in store for you in Part-3 of this article.

by Bishu Prusty (Radio Sai Team)

Graphics: Mohan Dora (Radio Sai Team)

What are your impressions about this article? Please share your feedback by writing to h2h@radiosai.org. Do not forget to mention your name and country.